[SPOILER ALERT] If you’re a fan of my podcast, and have not yet listened to Episode 159, I’m about to give away the ending. Listen first, if you don’t want to ruin the mystery.

[TRIGGER WARNING] In the course of discussing this episode, I use a word that some will find objectionable. If you believe certain words have an inherent power to harm people, stop reading here.

——

Couple months ago, I wrote a story for my podcast about the invention of the High Five. I called it, “He Was Just Trying to Get Home.” It’s a true story about the moment two baseball players named Dusty Baker and Glenn Burke spontaneously slapped their palms together at home plate in Dodger Stadium, moments after Dusty hit a late inning home run back in 1978. Dusty Baker and Glenn Burke were both black men. Glenn Burke, however, was not only black, he was gay – the first openly gay player to wear a major league uniform.

In the course of telling my version of this story, I made reference to the racism and bigotry that men like Baker and Burke encountered in the major leagues. I also referenced a comment attributed to Billy Martin, the coach of the Oakland A’s, for whom Glenn Burke briefly played. Specifically, I describe in my story, the moment when Billy Martin introduced Glenn Burke to his new teammates, as a “faggot.”

Shortly after the podcast aired, on August 18th, I received this note on my Facebook page, from Billy Martin, Jr.

Hi Mike,

I recently heard a podcast of yours that had some information about my father, Billy Martin. I would like to know who your sources were because I don’t believe that information was accurate and would love to speak to you about it.

Billy Martin, Jr.

Uh-oh…

I responded to Billy immediately, and provided him with a link to the specific article that referenced that comment. Here it is. The article was written by a guy named Peter Dreier, who attributes the specific quote to an outfielder named Claudell Washington.

A few hours later, Billy responded. He was very respectful, but steadfast in his defense of his father. Billy told me he spoke to several players who were on the team back in 1980, none of whom believed Claudell’s claim. Billy wrote, “Mike, I apologize for being so sensitive, but Reggie Jackson called my father a racist 15 years after he had passed, and Dad was absolutely the most colorless man I have ever known. He lost his job as a Yankee in 1957, because he beat up some bowlers for hurling racial slurs at Sammy Davis Junior. He and Mickey Mantle would not go inside a restaurant if they wouldn’t serve their teammate, Elston Howard. My father had lots of faults, but he couldn’t care less about someone’s race, creed, color, or sexual orientation. Billy Martin was all about winning.”

Over the next two months, Billy and I exchanged half a dozen emails. Our notes were always cordial, but Billy was always adamant – the incident I described in my podcast never happened. I have to say, I admired his certainty, and his determination to protect his father’s legacy. In fact, I offered to post our entire exchange on this page, word for word.

“Your desire to defend your father’s reputation speaks well of you,” I said. “Honestly, I think people should hear your side of the story in your own words.”

Billy replied a few days later.

“Thanks Mike, for all you time on this. Let me think about it. Problem is, someone has now added Claudell’s claim to my father’s Wikipedia page, as well as Glenn Burke’s. I’m trying to discern if letting it die down might be for the best. I don’t want something like this to preclude my dad from being inducted into the Hall of Fame.”

Oh, crap. I hadn’t thought of that.

As many of you know, “The Way I Heard It” is more than a cavalier title for a podcast that deals with historical figures – it’s also a disclaimer – a plea for my listeners to remember that anyone today can hop on the internet and find a source to confirm or deny any claim. Caveat emptor, in other words. However, after my exchanges with Billy, my clever title started to feel less like a call for skepticism, and more like an excuse for spreading gossip. After all, we’re talking about a man’s reputation here, and a reputation is a fragile thing.

The more I thought about this, the more uncomfortable I became. What exactly is my responsibility to the Martin family? I’m not a reporter with a column in a paper of record; I’m just a guy with a podcast and a Facebook page. Am I still obligated to verify the accuracy of Claudell Washington’s claim, before I share it with six million people? Or can I continue to point to my clever title and tell Billy Martin Jr, “Hey man, don’t blame me, that’s just the way I heard it?”

I had no good answer, so I did something I probably should have done before I recorded this episode – I read Glenn Burke’s book, “Out at Home: The True Story of Baseball’s First Openly Gay Player.” In it, I found a number of references that seemed to confirm that Billy Martin was in fact, not shy about using the word in question. I was not shocked by this. However, I also found this, from Glenn Burke himself:

“Billy Martin never called me a faggot to my face.”

Interesting. Does this mean Billy Martin never uttered the offending word? Of course not. Back in 1980, a lot of people used that word, and I’d have been surprised to learn that Billy Martin wasn’t among them. But Glenn Burke’s statement does change the plausibility of Claudell Washington claim. Because, if Glenn Burke never heard Billy Martin actually call him a “faggot,” then it would have been impossible for Billy Martin to have introduced him to the team in such a way.

A few days later, Billy wrote this.

Mike,

After speaking with several more players that were there during my father’s managerial term, I am now absolutely certain that my father did not say anything derogatory about Glenn Burke’s sexuality. I spoke to Catcher Mike Heath, outfielder Duane Murphy, traveling secretary Mickey Moribito, & clubhouse manager Steve Vucinich. They were all there during that 1980 spring training & all of them absolutely deny anything like that ever happened.

Thanks

Billy Martin Jr.

Okay. Let’s recap.

A reporter named John Dreier claimed that an outfielder named Claudell Washington said a manager named Billy Martin introduced the first openly gay man to play major league baseball, as a “faggot,” forty years ago. I then repeated that claim in a podcast about the invention of the High Five. Was I wrong to do so?

I think maybe I was. Not because I shared a claim I couldn’t personally verify, but because I forgot something. I forgot that we live in an age where our ancestors are held to a standard that didn’t exist when they were alive. An age where an accusation is enough to pass judgment. An age, where a man is considered guilty, if the internet says he is. I forgot that in this day and age, Billy Martin Jr. has good reason to worry about the way his father will be remembered.

Of course, Glenn Burke also had some things to say about the age in which he lived. Clearly, “the good old days” in major league baseball were a nightmare for people of color, and even worse for homosexuals. Doubly so, for a black homosexual. That’s why I wanted to write about it. I don’t like what major league baseball did to Glenn Burke, and I have no interest in soft pedaling the bigotry that drove him out of the sport he loved. But neither do I have any interest in contributing to the cancelation of Billy Martin, forty years after his alleged transgression. What’s the point in keeping this man out of the Hall of Fame? To me, it’s a bit like combatting racism by reducing certain slurs to a single letter. The “f-word?” The “n-word?” Seriously? I don’t use either term, and I don’t care for people who do. But imagine what Cooperstown would look like today, if all the inductees who ever uttered either of those words were removed. The Hall of Fame would be an empty corridor, just as Mt. Rushmore will be an empty slab of granite, if we allow this twisted logic to continue.

I was talking yesterday to my friend Susan, who suggested I write the High Five story. She said, “Mike, don’t beat yourself up over this. Until we have a time machine, arguments about the past will never be resolved.”

Susan’s right, but if I had access to such a machine, my first stop wouldn’t be 1980, to see precisely what Billy Martin said or didn’t say about Glenn Burke – it would be the future. I’d zip ahead a few decades from now to see if there were any statues left, and if so, whose monuments were on the chopping block. Seriously, what will the next generation of our woke descendants think of us? Which of our cherished institutions will turn out to be unforgivable transgressions, forty years from now? Eating animals? Aborting babies? Executing criminals? Which of the words we use today, will lead our sons and daughters to disavow us, when confronted with digital proof of our rhetorical depravity?

In the end, we’re all gonna have to decide who is worth remembering, and why. And on a personal level, I have to decide if The Way I Heard It still gives me enough cover to write the stories I want to write. I think so, because without a time machine, I’ll never be able to tell you “The Way It Was.” On the other hand, I have no desire to spread information that’s inaccurate, especially in this age of retroactive social justice. So, what to do? Keep writing, and hope for the best? Or step away from the keyboard and wait for that time machine?

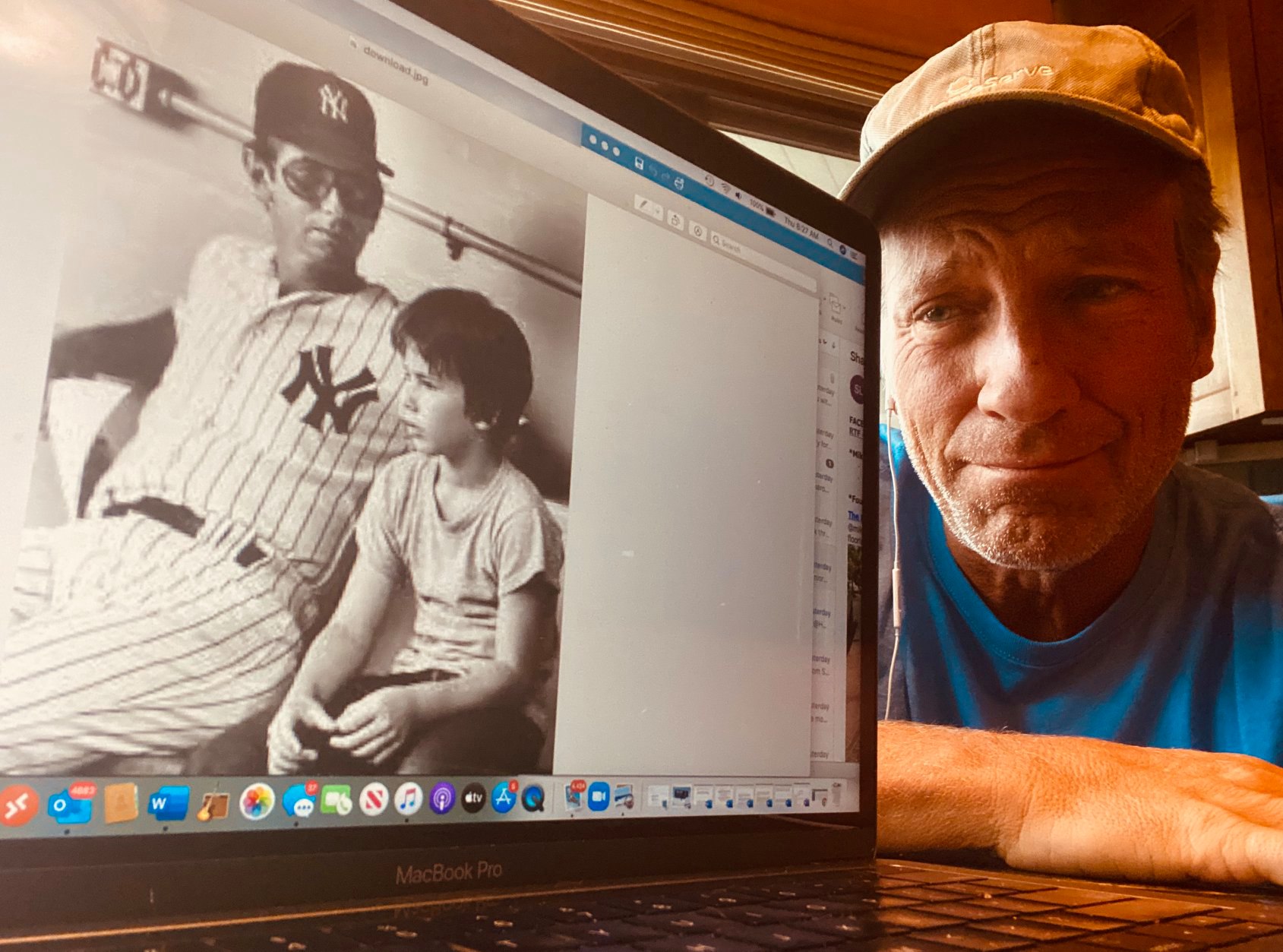

As a diehard Orioles fan, it kills me to say that these questions were inspired by a damn Yankee, but Billy Martin Jr has given me something to think about. I admire the way he’s come to his Dad’s defense, and I respect the way he protected his reputation. So, if the world is going to judge Billy Martin by unprovable accusations that I shared on my podcast, it seems only fair to share “the rest of the story,” from someone who actually knew the man. Which I hope this post has accomplished.

Mike

- For the record, I hope Billy Martin is inducted into The Hall of Fame. I have no idea what kind of man he really was, or what kind of naughty words he might have used in the clubhouse, forty years ago. But, the way I heard it, he was a pretty good second baseman, and one hell of a manager. George Steinbrenner, on the other hand?

Don’t even get me started…