Yesterday morning, in a restroom at the airport in Kona, a man recognized me while I was standing at the urinal.

“Hey,” he said, “you’re the Dirty Jobs Guy, right?”

Since we were both engaged in the same activity, and since there was no point in denying it, I nodded and said, “Yes, well, everybody has to be somebody.”

The man said, “Can I ask you a question?”

“Sure,” I said. I knew exactly what the question would be, and sensed I’d be standing there long enough to answer it. But the man beside me didn’t want to know what my dirtiest job was. He wanted to know when my mother’s next book was coming out.

“Later this year,” I said. “Or, whenever she gets around to it. She’s pretty busy these days, what with her speaking schedule and her many public appearances.”

The man chuckled. “Well, give her my regards, and tell her she’s got a big fan on the big island.”

I nodded and promised to deliver the message. Then we stood there for another minute or so, concentrating, hoping the plane wouldn’t leave without us.

I’m not sure why I was surprised by the man’s question. Until yesterday, Hawaii was one of the only states where I haven’t been asked to deliver a similar message. This is because Hawaii is one of the only states I haven’t visited in the last five years. Everywhere else I’ve been – and I mean everywhere – people have pulled me aside to say something nice about Peggy Rowe, and then, instruct me to pass it on.

Last week in Oklahoma, it was an Uber driver named Ruth, who called my mother her “spirit animal.”

“Tell her I said so, would you.”

“Sure,” I said.

The week before that, in New York, it was a bellman named Ralph who wanted me to know that my father was a “very lucky man.”

“I’ll tell him you said so,” I said.

“Tell your mother,” he said. “Your father already knows.”

“Indeed,” I said. “I’ll pass it on.”

“Do that,” he told me. “Your mother is a peach.”

Last month in Florida, it was a young woman from London with whom I shared an elevator. I didn’t get her name, but she sounded like Eliza Doolittle.

“Oh my God,” she said. “I absolutely love your mum.”

“That’s nice,” I said. “I’ll let her know.”

“No,” she said. “You don’t understand. I freaking LOVE her.”

She was kind of wide-eyed and screaming, as I stepped into the hallway and wished her a pleasant day. I could still hear her yelling from behind the door after it slid shut. “I FREAKING LOVE LOVE LOVE HER! TELL HER I LOVE HER…”

I yelled back through the closed door. “OKAY! I’LL TELL HER!”

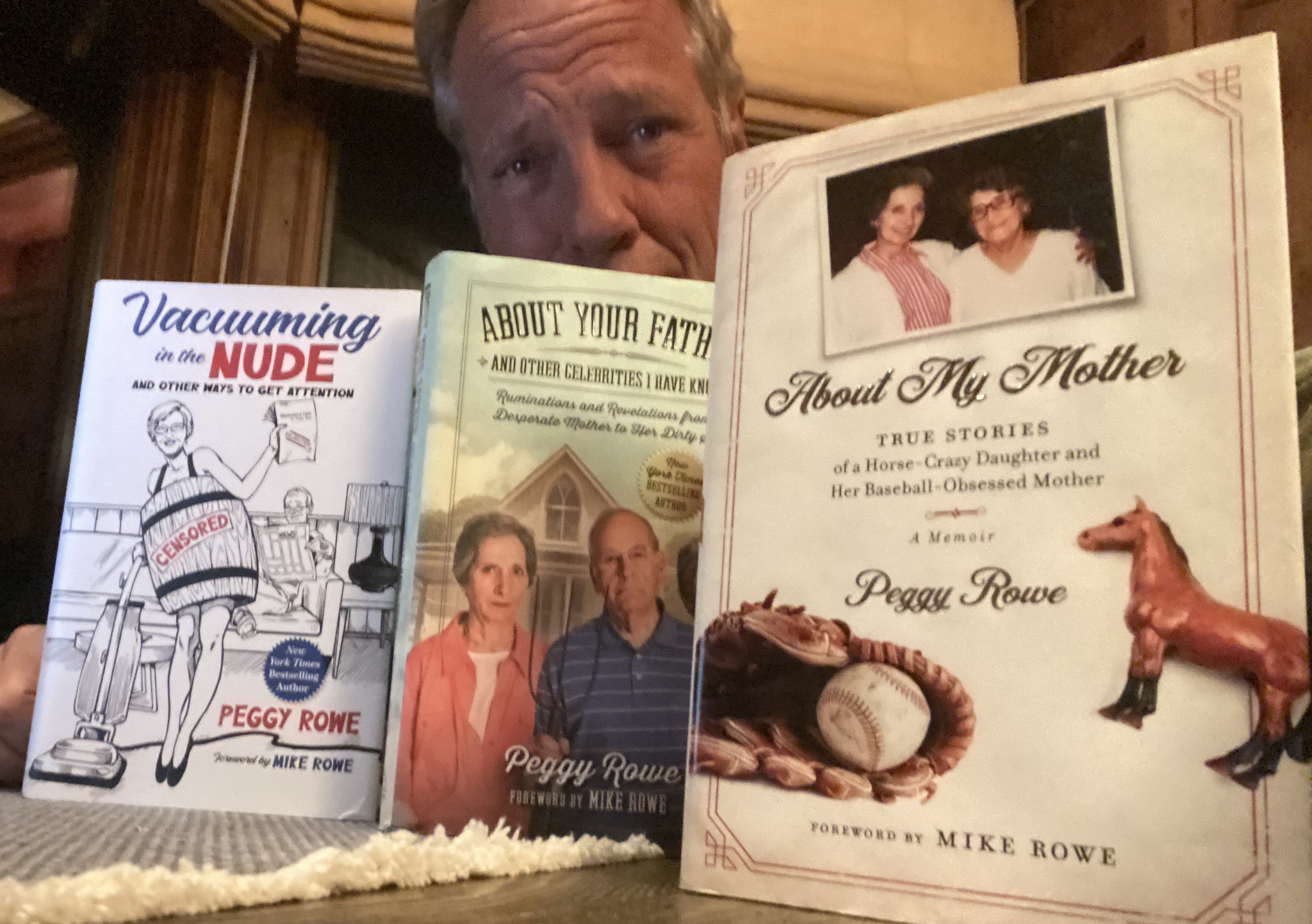

Maybe people are inspired by the true story of a woman who wrote every day for sixty years before finally becoming a bestselling author at the age of eighty? That’s the story behind her third book, and it sold a bunch of copies, so maybe her remarkable persistence has struck a chord with the masses? Or maybe, people see something in my mother that reminds them of their own mom, and are powerless not to tell me? Whatever the reason, the verdict is in – people seem to like my mom.

On her Facebook page, thousands of fans ask her advice on a variety of topics. She rarely gives any, but when she does, it’s always worth sharing. (“Always encourage the people you love, and the people you don’t.” “Always mean what you say.” “Never threaten your children, but if you do, you’d better follow through.”)

On my podcast, she’s become the most requested guest, and the source of much feedback. “You know, Mike, your mother should have her own podcast. Maybe she should be hosting your show?”

At the retirement community where she and my dad live, she’s in constant demand, and her publisher now worries that her social calendar might be slowing down her literary output. “It’s important to write every day,” Jonathan tells her. “Your next book won’t write itself!”

“I know,” she says, “I know. But John’s bocce ball team is in the finals, and I can’t concentrate with all the excitement around here!”

Obviously, it’s a sad day for me when strange men in public toilets no longer ask about my dirtiest job, or my own book, or my next project, or my plans for the future. But I suppose, if I’m to be upstaged at this point in my career, it should be by my favorite author of all time.

So, here’s to you, Mom, for postponing your dream of becoming a writer for sixty years, in order to become the mother I’m now obliged to share with the world. Like everyone else, I’ll always be in your debt, and no matter where I roam, always grateful to be among those who absolutely freakin love you.